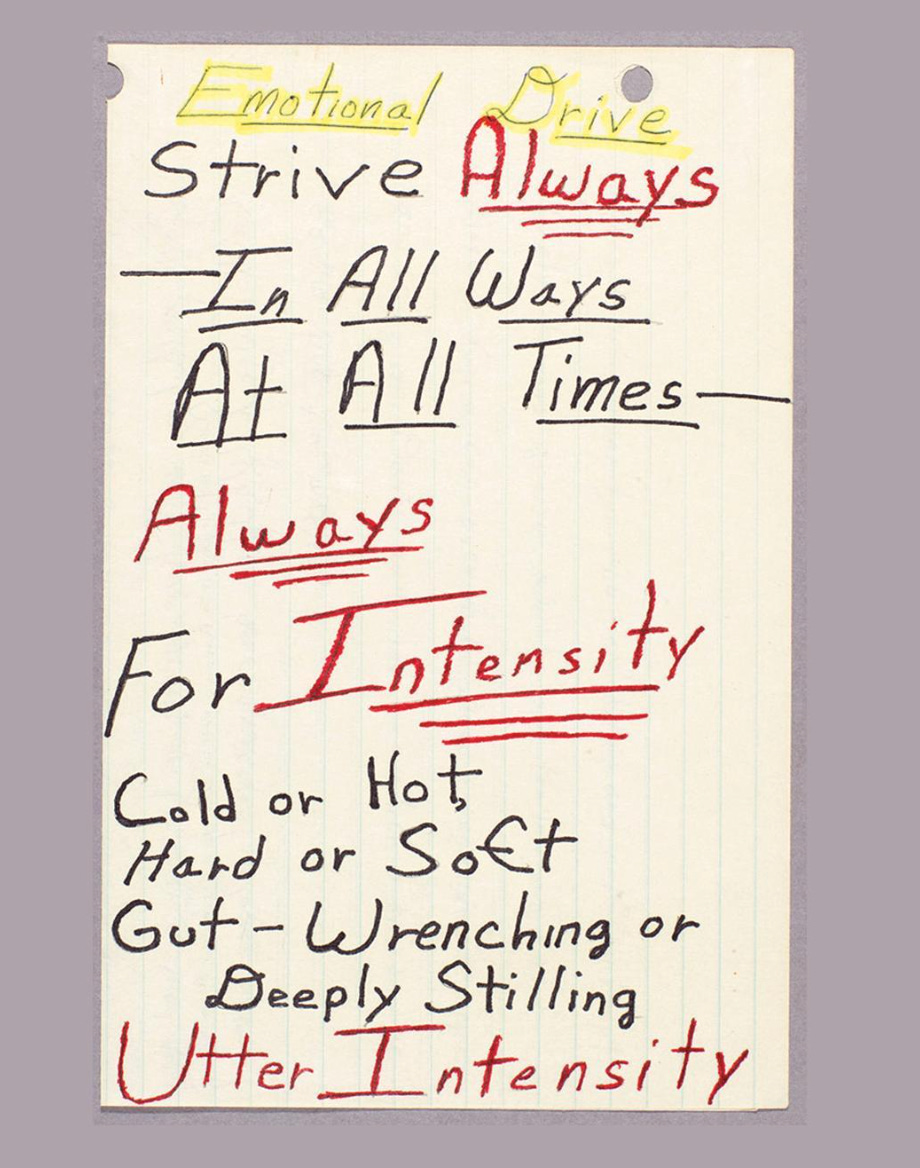

For Intensity

How to Approach Cultivating a Writing Practice

Back in August, I wrote a little about process and practice, stating that

Process refers to the means by which something develops or moves forward, while practice is a word for the particular kind of repetition out of which process can emerge. You could say that process is housed within practice.

And I received a comment from my wonderful writer colleague

that complicated this thought; Rami questioned the order within which I had assigned these concepts to stand, and suggested that perhaps they “do not nest but are co-created, they are forever looping back on themselves.”I’m finding this a generative reframing of my initial thoughts, and have been turning this conceptualization of process/practice as chiasmatic feedback look over and back again in my mind since. It makes sense that these ways of being and growing (with) one’s writing would endlessly inform one another into further stages of iteration.

I was recently asked whether I had any tips on stepping into a writing practice, and it struck me that this could also be an opportunity to think more intentionally about the relationship between process and practice. Some of the approaches I share below are more pragmatic and practical, and others are more about mindset shifts and one’s overall philosophical approach to the work. Most of these tips were drawn out from what I’ve already written, which I elaborate on and link to where relevant.

Ten Tips on Developing a Writing Practice

Everything is research: my approach here is to get you started from as broad and abundant a mindset as possible. Anything and everything can be the basis for your writing, which is why it’s important to take notes on what you notice and on the ways you’re interacting with your environment. Get curious, and notice what you’re most drawn to and interested in spending more time with.

Start with specificity: it may help to begin with a writing prompt or some other kind of structuring limitation. Some years ago, I heard that in one study, children playing on the beach were more likely to go farther out when given a direct boundary than when told they could play anywhere they wanted. We enjoy pushing our limits, but we have to have a sense of what they are, first. Our minds cannot conceptualize infinite possibility. You can even make up your own prompts by choosing a line from a nearby book at random and writing something in response. Or, you can give yourself a writing constraint, such as avoiding adverbs or writing in a standard poetic form like a sonnet or haiku.

Use timers to just get started against the fear of the blank page: for me, starting is often the hardest part. Setting a timer for ten minutes and doing some freewriting, stream-of-consciousness style, can be really helpful in overcoming my own doubts and fears that the writing is just not going to work this time.

At the same time, remember that you’re never truly starting with a blank page: while there’s indeed something intimidating about the white expanse of the surface in front of you, it may help to recall that, in one iteration of Jewish cosmology (Bereshit, known in English as the Book of Genesis), creation emerges not from nothing but from a primordial chaos. For me, this actually lowers the stakes—I’m not starting from a totally blank slate but from the chaos of my innermost thoughts and feelings, which I can allow to spill out onto the page in front of me. Because, chaos? Well, chaos can be edited. Blank pages can’t. In other words, it matters less what you put onto the page to start and more that you put something, anything, there in the first place.

Play around with your mode of writing: in a wonderful interview with Amina Cain, Sofia Samatar says, “The feeling of scribbling in a journal creates an immediacy, a sense that anything might happen.” But don’t necessarily rule out typing either, whether on a laptop or on your phone. Experiment with what makes it easiest for you to move into a state of play. It’s crucial that it feel as low-stakes as possible. Don’t use your most aspirational blank notebook if you’re afraid to “ruin” it when a pad of paper from the dollar store works just as well.

Get into the physicality of writing: Gloria Anzaldúa talks in her book Light in the Dark/Luz en lo Oscuro about writing as “gestures of the body,” saying that “Writing is not about being in your head; it’s about being in your body. The body responds physically, emotionally, and intellectually to external and internal stimuli, and writing records, orders, and theorizes about these responses.” Stay curious about the ways writing is an embodied process, from the physical task of getting words down on the page whether by pen or keyboard, to remembering that stretching and back support are good writerly friends.

Release perfectionism and the desire for stasis: your writing will never be as perfect as your idea is in your head, and that’s a good thing. Because your writing is a living, breathing thing, and, chiefly, something that can be read by other people.

Align your actions with your values: you might not be the kind of person who writes every day, and that’s okay! Maybe being compassionate with yourself is more important right now than unyielding self-discipline (and personally, I’m always in favor of more self-compassion). Ask yourself what actually matters to you, and then make choices that reflect those values.

Remember that this is relational work: no one ever writes or thinks or speaks in isolation. To write is to understand that there is some kind of essential and dynamic relation between the world, the self, and the creative process. You’re never truly alone.

Don’t be afraid to fuck it up: in her aforementioned interview with Amina Cain, Sofia Samatar asks, after Clarice Lispector, “For what purpose am I saving myself,” following this inquiry with a charge, á la Octavia Butler, towards intensity. “Cold or hot, hard or soft, gut-wrenching or deeply stilling, utter intensity!” In other words, don’t fear commitment. Besides, with writing, unlike with painting or many other artistic disciplines, it’s possible to go back to earlier versions if what you’re working on isn’t really working out. So there’s really no need to hold back for fear you’ll lose something.

With process and practice co-iterative and inextricable from one another, it stands to reason that changes to one will impact the other. Getting started engaging with a writing practice, in other words, will have knock-on effects for your writing process, which may itself evolve and change depending on what exactly you’re writing.

If you’re interested in learning more about cultivating both practice and process in nonfiction writing, I’ll soon be launching a two hour workshop on brainstorming, developing, and writing essays in the mode of cultural criticism, to take place in November on Zoom.

And if fiction is more your style, don’t worry, I have more news on that front coming soon!

I am so delighted to have offered a generative thought, and see you run with it! Thanks for the shout 🙏🏻 and your excellent suggestions.